The Arch That Cut the Sky — Part Two

Tsamouris, the Fastener Specialists©

Part Two

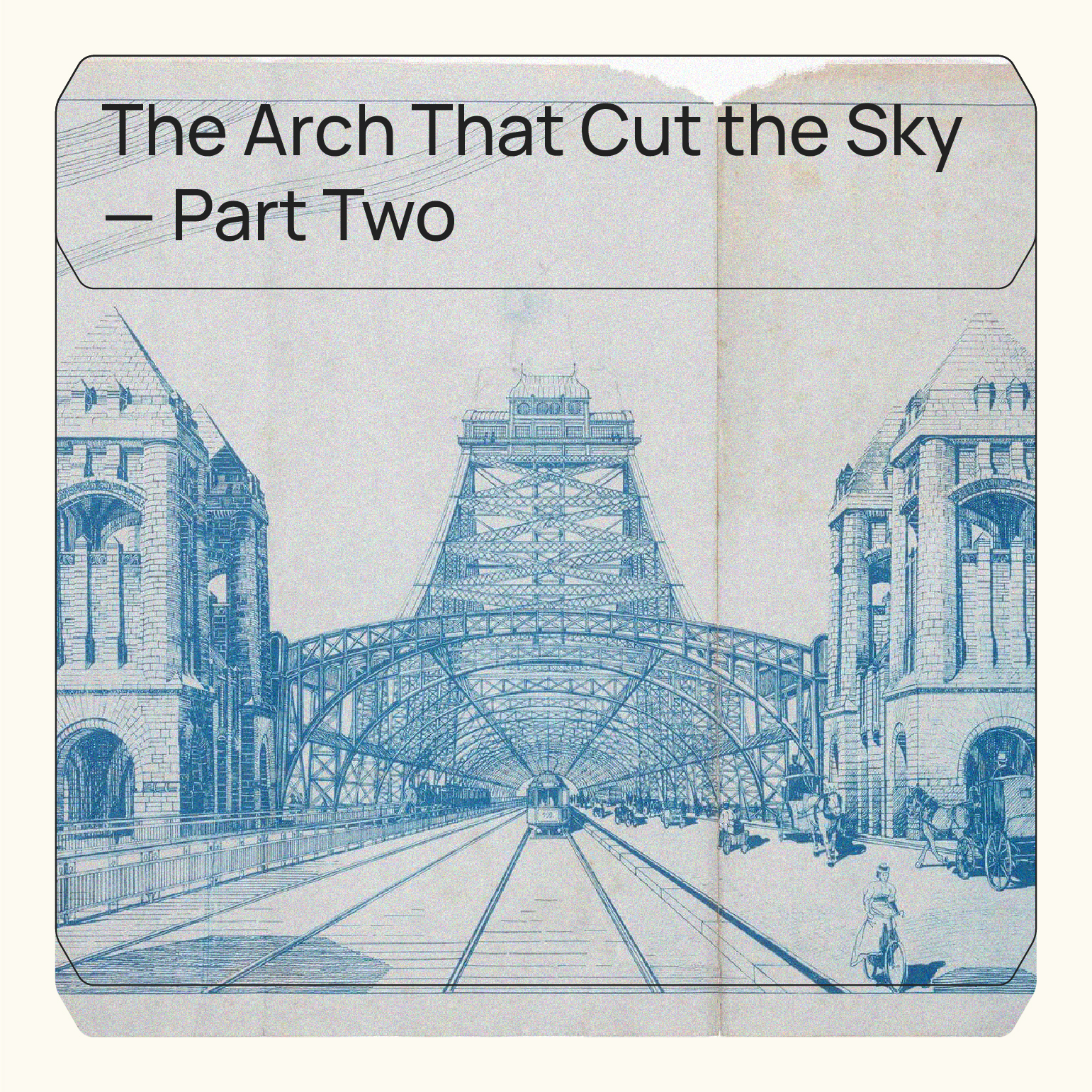

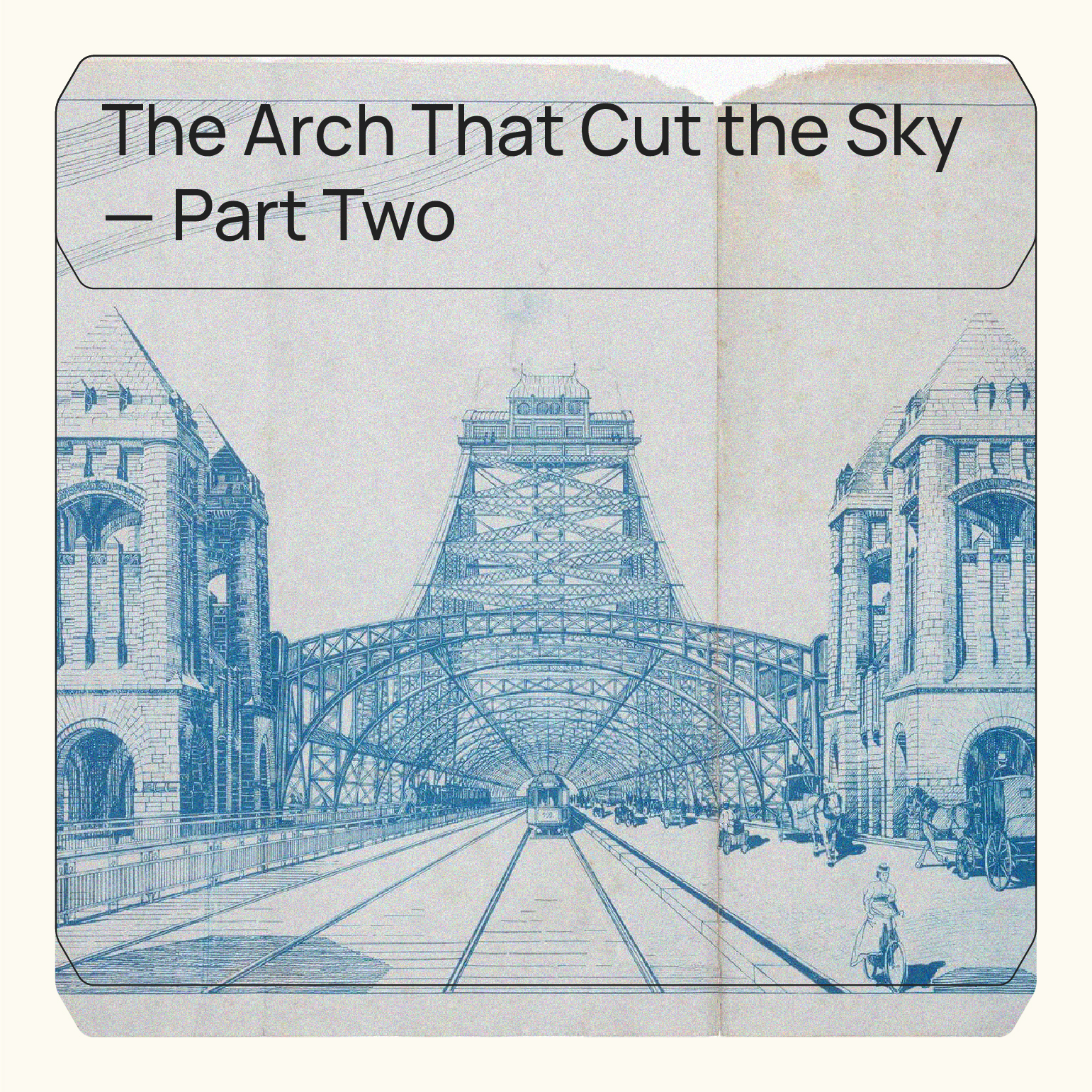

As the 20th century dawned, Sydney's rapid growth and the outbreak of the bubonic plague in the early 1900s made it clear that the city was in desperate need of a permanent harbour crossing. The public works project would be the largest ever attempted in New South Wales, requiring the demolition of shanties and shacks in North Sydney and Millers Point to make way for the bridge and an underground railway system.

The government held four separate bridge design competitions between 1900 and 1924, attracting more than 20 submissions from national and international engineering companies. The designs were exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets, but none would succeed in meeting the rigorous demands of Sydney's citizens and city planners.

Two visionary engineers emerged as the strongest contenders: Norman Selfe and John Job Crew Bradfield. Selfe, an engineer, naval architect, and inventor, had conceived of a harbour crossing decades before the bridge we know today was built. His 1901 design for a steel cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to McMahons Point was accepted by the NSW Government, but political tides and economic factors prevented its construction. Selfe won a second competition outright in 1903, but his vision was again lost to the vagaries of Sydney's politics and a change of government in 1904.

Enter John Bradfield, a civil engineer with a brilliant academic mind. Bradfield was a paradox: bold and visionary as a planner, but cautious as an engineer. In 1912, he submitted a design for a cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to Milsons Point, which received government approval. However, the onset of World War I delayed any construction efforts.

In the post-war years, Bradfield traveled the world researching bridge designs, eventually discovering an arch bridge in New York City that would be suitable for the enormous span of Sydney Harbour and more cost-effective than a cantilever bridge. With the help of his tenacious secretary, Kathleen Butler, known as the "bridge girl," Bradfield convinced Sydney's politicians that a single-arch bridge could be built without blocking the city's vital shipping lanes.

After decades of political maneuvering and delays, the Harbour Bridge Act was finally carried in 1924. That same year, Bradfield recommended accepting the tender of Dorman Long & Co. of Middlesbrough, England, whose design for a two-hinged arch with piers and pylons in granite-faced concrete was judged to be the best.

Bradfield's vision was set to become a reality, as he announced in a speech in 1921: "The tender recommended, for the two-hinged arch bridge with granite masonry facing, is my design as sanctioned by Parliament and as submitted for tenders… Due to our gallant soldiers, Australia has recently been acclaimed a nation. In the upbuilding of any nation the land slowly moulds the people, the people with patient toil alter the face of the landscape… They humanise the landscape after their own image…"

The path was now clear for the most ambitious construction project Australia had ever seen, a task that would take eight years, six million hand-driven rivets, 1,400 laborers, and the lives of 16 workers. In the next chapter of this story, we will meet the people who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, transforming the visions of countless planners, designers, dreamers, and engineers into a magnificent reality.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Part Two

As the 20th century dawned, Sydney's rapid growth and the outbreak of the bubonic plague in the early 1900s made it clear that the city was in desperate need of a permanent harbour crossing. The public works project would be the largest ever attempted in New South Wales, requiring the demolition of shanties and shacks in North Sydney and Millers Point to make way for the bridge and an underground railway system.

The government held four separate bridge design competitions between 1900 and 1924, attracting more than 20 submissions from national and international engineering companies. The designs were exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets, but none would succeed in meeting the rigorous demands of Sydney's citizens and city planners.

Two visionary engineers emerged as the strongest contenders: Norman Selfe and John Job Crew Bradfield. Selfe, an engineer, naval architect, and inventor, had conceived of a harbour crossing decades before the bridge we know today was built. His 1901 design for a steel cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to McMahons Point was accepted by the NSW Government, but political tides and economic factors prevented its construction. Selfe won a second competition outright in 1903, but his vision was again lost to the vagaries of Sydney's politics and a change of government in 1904.

Enter John Bradfield, a civil engineer with a brilliant academic mind. Bradfield was a paradox: bold and visionary as a planner, but cautious as an engineer. In 1912, he submitted a design for a cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to Milsons Point, which received government approval. However, the onset of World War I delayed any construction efforts.

In the post-war years, Bradfield traveled the world researching bridge designs, eventually discovering an arch bridge in New York City that would be suitable for the enormous span of Sydney Harbour and more cost-effective than a cantilever bridge. With the help of his tenacious secretary, Kathleen Butler, known as the "bridge girl," Bradfield convinced Sydney's politicians that a single-arch bridge could be built without blocking the city's vital shipping lanes.

After decades of political maneuvering and delays, the Harbour Bridge Act was finally carried in 1924. That same year, Bradfield recommended accepting the tender of Dorman Long & Co. of Middlesbrough, England, whose design for a two-hinged arch with piers and pylons in granite-faced concrete was judged to be the best.

Bradfield's vision was set to become a reality, as he announced in a speech in 1921: "The tender recommended, for the two-hinged arch bridge with granite masonry facing, is my design as sanctioned by Parliament and as submitted for tenders… Due to our gallant soldiers, Australia has recently been acclaimed a nation. In the upbuilding of any nation the land slowly moulds the people, the people with patient toil alter the face of the landscape… They humanise the landscape after their own image…"

The path was now clear for the most ambitious construction project Australia had ever seen, a task that would take eight years, six million hand-driven rivets, 1,400 laborers, and the lives of 16 workers. In the next chapter of this story, we will meet the people who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, transforming the visions of countless planners, designers, dreamers, and engineers into a magnificent reality.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

The Arch That Cut the Sky — Part Two

Tsamouris, the Fastener Specialists©

Part Two

As the 20th century dawned, Sydney's rapid growth and the outbreak of the bubonic plague in the early 1900s made it clear that the city was in desperate need of a permanent harbour crossing. The public works project would be the largest ever attempted in New South Wales, requiring the demolition of shanties and shacks in North Sydney and Millers Point to make way for the bridge and an underground railway system.

The government held four separate bridge design competitions between 1900 and 1924, attracting more than 20 submissions from national and international engineering companies. The designs were exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets, but none would succeed in meeting the rigorous demands of Sydney's citizens and city planners.

Two visionary engineers emerged as the strongest contenders: Norman Selfe and John Job Crew Bradfield. Selfe, an engineer, naval architect, and inventor, had conceived of a harbour crossing decades before the bridge we know today was built. His 1901 design for a steel cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to McMahons Point was accepted by the NSW Government, but political tides and economic factors prevented its construction. Selfe won a second competition outright in 1903, but his vision was again lost to the vagaries of Sydney's politics and a change of government in 1904.

Enter John Bradfield, a civil engineer with a brilliant academic mind. Bradfield was a paradox: bold and visionary as a planner, but cautious as an engineer. In 1912, he submitted a design for a cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to Milsons Point, which received government approval. However, the onset of World War I delayed any construction efforts.

In the post-war years, Bradfield traveled the world researching bridge designs, eventually discovering an arch bridge in New York City that would be suitable for the enormous span of Sydney Harbour and more cost-effective than a cantilever bridge. With the help of his tenacious secretary, Kathleen Butler, known as the "bridge girl," Bradfield convinced Sydney's politicians that a single-arch bridge could be built without blocking the city's vital shipping lanes.

After decades of political maneuvering and delays, the Harbour Bridge Act was finally carried in 1924. That same year, Bradfield recommended accepting the tender of Dorman Long & Co. of Middlesbrough, England, whose design for a two-hinged arch with piers and pylons in granite-faced concrete was judged to be the best.

Bradfield's vision was set to become a reality, as he announced in a speech in 1921: "The tender recommended, for the two-hinged arch bridge with granite masonry facing, is my design as sanctioned by Parliament and as submitted for tenders… Due to our gallant soldiers, Australia has recently been acclaimed a nation. In the upbuilding of any nation the land slowly moulds the people, the people with patient toil alter the face of the landscape… They humanise the landscape after their own image…"

The path was now clear for the most ambitious construction project Australia had ever seen, a task that would take eight years, six million hand-driven rivets, 1,400 laborers, and the lives of 16 workers. In the next chapter of this story, we will meet the people who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, transforming the visions of countless planners, designers, dreamers, and engineers into a magnificent reality.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Part Two

As the 20th century dawned, Sydney's rapid growth and the outbreak of the bubonic plague in the early 1900s made it clear that the city was in desperate need of a permanent harbour crossing. The public works project would be the largest ever attempted in New South Wales, requiring the demolition of shanties and shacks in North Sydney and Millers Point to make way for the bridge and an underground railway system.

The government held four separate bridge design competitions between 1900 and 1924, attracting more than 20 submissions from national and international engineering companies. The designs were exhibited in the Queen Victoria Markets, but none would succeed in meeting the rigorous demands of Sydney's citizens and city planners.

Two visionary engineers emerged as the strongest contenders: Norman Selfe and John Job Crew Bradfield. Selfe, an engineer, naval architect, and inventor, had conceived of a harbour crossing decades before the bridge we know today was built. His 1901 design for a steel cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to McMahons Point was accepted by the NSW Government, but political tides and economic factors prevented its construction. Selfe won a second competition outright in 1903, but his vision was again lost to the vagaries of Sydney's politics and a change of government in 1904.

Enter John Bradfield, a civil engineer with a brilliant academic mind. Bradfield was a paradox: bold and visionary as a planner, but cautious as an engineer. In 1912, he submitted a design for a cantilever bridge from Dawes Point to Milsons Point, which received government approval. However, the onset of World War I delayed any construction efforts.

In the post-war years, Bradfield traveled the world researching bridge designs, eventually discovering an arch bridge in New York City that would be suitable for the enormous span of Sydney Harbour and more cost-effective than a cantilever bridge. With the help of his tenacious secretary, Kathleen Butler, known as the "bridge girl," Bradfield convinced Sydney's politicians that a single-arch bridge could be built without blocking the city's vital shipping lanes.

After decades of political maneuvering and delays, the Harbour Bridge Act was finally carried in 1924. That same year, Bradfield recommended accepting the tender of Dorman Long & Co. of Middlesbrough, England, whose design for a two-hinged arch with piers and pylons in granite-faced concrete was judged to be the best.

Bradfield's vision was set to become a reality, as he announced in a speech in 1921: "The tender recommended, for the two-hinged arch bridge with granite masonry facing, is my design as sanctioned by Parliament and as submitted for tenders… Due to our gallant soldiers, Australia has recently been acclaimed a nation. In the upbuilding of any nation the land slowly moulds the people, the people with patient toil alter the face of the landscape… They humanise the landscape after their own image…"

The path was now clear for the most ambitious construction project Australia had ever seen, a task that would take eight years, six million hand-driven rivets, 1,400 laborers, and the lives of 16 workers. In the next chapter of this story, we will meet the people who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, transforming the visions of countless planners, designers, dreamers, and engineers into a magnificent reality.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Latest News