The Arch That Cut the Sky — Part Three

Tsamouris, the Fastener Specialists©

Part Three

With loans that would take the city 55 years to pay off, construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge commenced on 28 July 1923. The scale of the project was immense, requiring eight years, 1,400 laborers, six million hand-driven rivets connecting roughly 52,800 tonnes of steel beams, 272,000 liters of paint, and, tragically, the lives of 16 workers. Upon completion, it would stand as the largest single-arch bridge in the world.

Bradfield's vision for the Bridge was just one part of his grand plan to modernize Sydney's transport system, which included an electrified suburban railway spanning above and below ground to serve the city's growing population. The granite for the Bridge's decorative pylons came from Moruya, the sand from the Nepean River, and the cement from Kandos, while the majority of the steel was imported from England, with only 20% locally fabricated in Newcastle.

The Bridge provided much-needed employment during the Great Depression, becoming known as the "iron lung" for its massive injection into the economy. The workforce was diverse, including English engineers, Scottish and Italian stonemasons, American, British, and European riggers, and Irish and English boilermakers and machinists. The government favored giving work to war veterans, union members, and men with families, and reduced working hours from 44 to 33 to spread the available jobs among more people.

However, the physically grueling and dangerous nature of the work led to numerous accidents and fatalities. Reg Saunders, a 19-year-old apprentice stonemason at the Moruya Quarry, described the bloody initiation process that lasted for months. Workers standing on the Bridge hundreds of feet in the air, secured only by ropes, had to catch newly forged, scalding-hot metal rivets and bolts in buckets of water and hammer them into the beams, risking injury or death from falling objects.

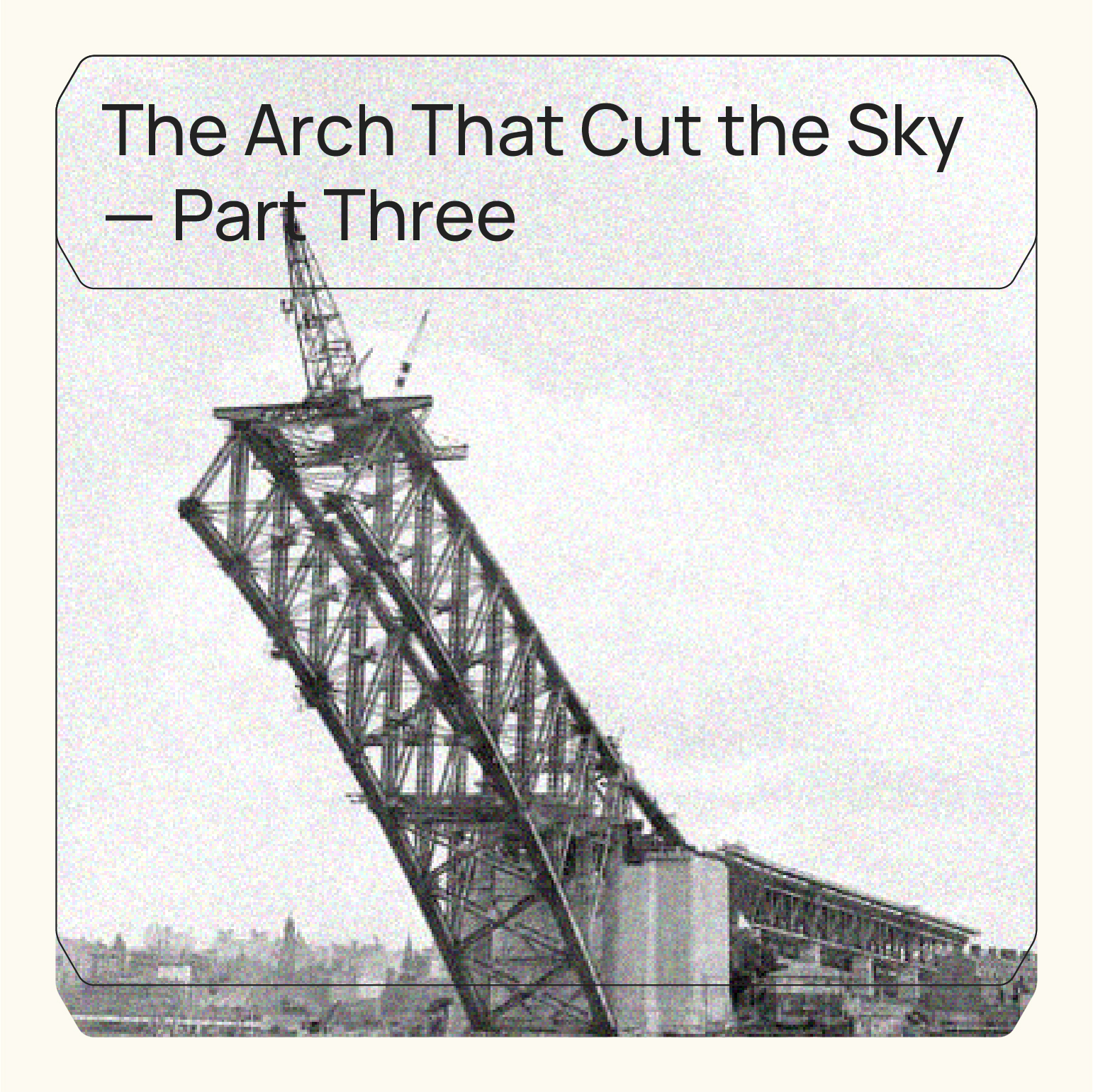

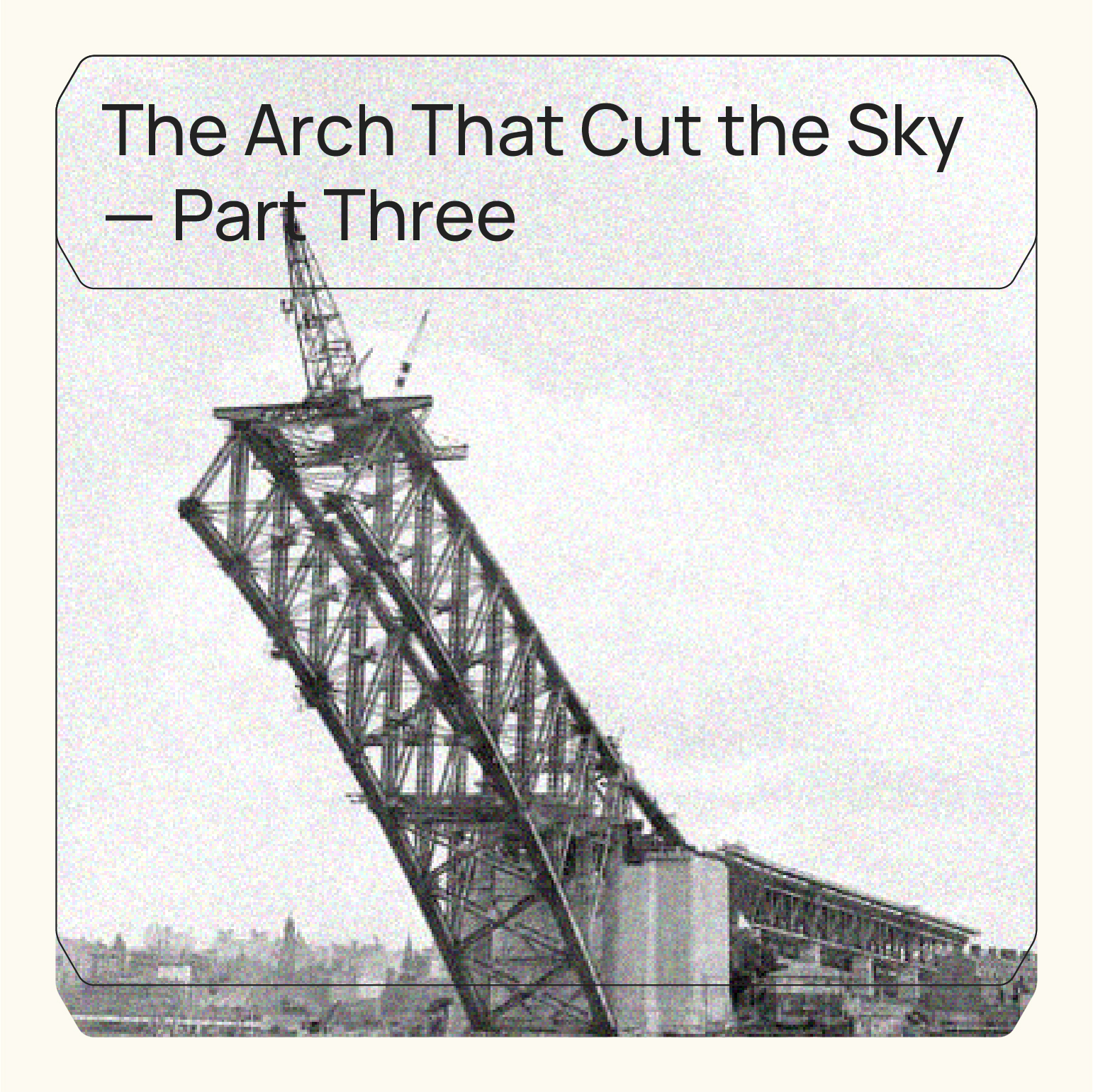

In 1928, construction of the steel arch itself began, with concrete pylons rising on either side of the harbor. It would take two years for the arches to touch in the middle, forming a structure weighing 39,000 tonnes. The feat caused great anxiety among the engineers, as such an architectural achievement had never been attempted before.

The arch was self-supporting, allowing the giant cables to be removed—a historic day commemorated by the raising of British and Australian flags on both sides of the Bridge. With the arch completed, construction proceeded swiftly. By June 1931, the deck was in place and topped with asphalt, and rails were laid for trams and trains. In January 1932, the final piece of granite was laid on the northwest pylon.

The Bridge's first test came in February, with a load-testing using 96 steam locomotives laid end-to-end atop its deck. Having passed these stress tests, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was declared safe for traffic and ready to welcome the sea of humanity awaiting the harbor crossing.

On 19 March 1932, after decades of political wrangling, upheaval, and incredible feats of construction, the Sydney Harbour Bridge would finally open to the public in a grand spectacle that included fireworks and an unexpected interruption equally as explosive as the planned festivities.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Part Three

With loans that would take the city 55 years to pay off, construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge commenced on 28 July 1923. The scale of the project was immense, requiring eight years, 1,400 laborers, six million hand-driven rivets connecting roughly 52,800 tonnes of steel beams, 272,000 liters of paint, and, tragically, the lives of 16 workers. Upon completion, it would stand as the largest single-arch bridge in the world.

Bradfield's vision for the Bridge was just one part of his grand plan to modernize Sydney's transport system, which included an electrified suburban railway spanning above and below ground to serve the city's growing population. The granite for the Bridge's decorative pylons came from Moruya, the sand from the Nepean River, and the cement from Kandos, while the majority of the steel was imported from England, with only 20% locally fabricated in Newcastle.

The Bridge provided much-needed employment during the Great Depression, becoming known as the "iron lung" for its massive injection into the economy. The workforce was diverse, including English engineers, Scottish and Italian stonemasons, American, British, and European riggers, and Irish and English boilermakers and machinists. The government favored giving work to war veterans, union members, and men with families, and reduced working hours from 44 to 33 to spread the available jobs among more people.

However, the physically grueling and dangerous nature of the work led to numerous accidents and fatalities. Reg Saunders, a 19-year-old apprentice stonemason at the Moruya Quarry, described the bloody initiation process that lasted for months. Workers standing on the Bridge hundreds of feet in the air, secured only by ropes, had to catch newly forged, scalding-hot metal rivets and bolts in buckets of water and hammer them into the beams, risking injury or death from falling objects.

In 1928, construction of the steel arch itself began, with concrete pylons rising on either side of the harbor. It would take two years for the arches to touch in the middle, forming a structure weighing 39,000 tonnes. The feat caused great anxiety among the engineers, as such an architectural achievement had never been attempted before.

The arch was self-supporting, allowing the giant cables to be removed—a historic day commemorated by the raising of British and Australian flags on both sides of the Bridge. With the arch completed, construction proceeded swiftly. By June 1931, the deck was in place and topped with asphalt, and rails were laid for trams and trains. In January 1932, the final piece of granite was laid on the northwest pylon.

The Bridge's first test came in February, with a load-testing using 96 steam locomotives laid end-to-end atop its deck. Having passed these stress tests, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was declared safe for traffic and ready to welcome the sea of humanity awaiting the harbor crossing.

On 19 March 1932, after decades of political wrangling, upheaval, and incredible feats of construction, the Sydney Harbour Bridge would finally open to the public in a grand spectacle that included fireworks and an unexpected interruption equally as explosive as the planned festivities.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

The Arch That Cut the Sky — Part Three

Tsamouris, the Fastener Specialists©

Part Three

With loans that would take the city 55 years to pay off, construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge commenced on 28 July 1923. The scale of the project was immense, requiring eight years, 1,400 laborers, six million hand-driven rivets connecting roughly 52,800 tonnes of steel beams, 272,000 liters of paint, and, tragically, the lives of 16 workers. Upon completion, it would stand as the largest single-arch bridge in the world.

Bradfield's vision for the Bridge was just one part of his grand plan to modernize Sydney's transport system, which included an electrified suburban railway spanning above and below ground to serve the city's growing population. The granite for the Bridge's decorative pylons came from Moruya, the sand from the Nepean River, and the cement from Kandos, while the majority of the steel was imported from England, with only 20% locally fabricated in Newcastle.

The Bridge provided much-needed employment during the Great Depression, becoming known as the "iron lung" for its massive injection into the economy. The workforce was diverse, including English engineers, Scottish and Italian stonemasons, American, British, and European riggers, and Irish and English boilermakers and machinists. The government favored giving work to war veterans, union members, and men with families, and reduced working hours from 44 to 33 to spread the available jobs among more people.

However, the physically grueling and dangerous nature of the work led to numerous accidents and fatalities. Reg Saunders, a 19-year-old apprentice stonemason at the Moruya Quarry, described the bloody initiation process that lasted for months. Workers standing on the Bridge hundreds of feet in the air, secured only by ropes, had to catch newly forged, scalding-hot metal rivets and bolts in buckets of water and hammer them into the beams, risking injury or death from falling objects.

In 1928, construction of the steel arch itself began, with concrete pylons rising on either side of the harbor. It would take two years for the arches to touch in the middle, forming a structure weighing 39,000 tonnes. The feat caused great anxiety among the engineers, as such an architectural achievement had never been attempted before.

The arch was self-supporting, allowing the giant cables to be removed—a historic day commemorated by the raising of British and Australian flags on both sides of the Bridge. With the arch completed, construction proceeded swiftly. By June 1931, the deck was in place and topped with asphalt, and rails were laid for trams and trains. In January 1932, the final piece of granite was laid on the northwest pylon.

The Bridge's first test came in February, with a load-testing using 96 steam locomotives laid end-to-end atop its deck. Having passed these stress tests, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was declared safe for traffic and ready to welcome the sea of humanity awaiting the harbor crossing.

On 19 March 1932, after decades of political wrangling, upheaval, and incredible feats of construction, the Sydney Harbour Bridge would finally open to the public in a grand spectacle that included fireworks and an unexpected interruption equally as explosive as the planned festivities.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Part Three

With loans that would take the city 55 years to pay off, construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge commenced on 28 July 1923. The scale of the project was immense, requiring eight years, 1,400 laborers, six million hand-driven rivets connecting roughly 52,800 tonnes of steel beams, 272,000 liters of paint, and, tragically, the lives of 16 workers. Upon completion, it would stand as the largest single-arch bridge in the world.

Bradfield's vision for the Bridge was just one part of his grand plan to modernize Sydney's transport system, which included an electrified suburban railway spanning above and below ground to serve the city's growing population. The granite for the Bridge's decorative pylons came from Moruya, the sand from the Nepean River, and the cement from Kandos, while the majority of the steel was imported from England, with only 20% locally fabricated in Newcastle.

The Bridge provided much-needed employment during the Great Depression, becoming known as the "iron lung" for its massive injection into the economy. The workforce was diverse, including English engineers, Scottish and Italian stonemasons, American, British, and European riggers, and Irish and English boilermakers and machinists. The government favored giving work to war veterans, union members, and men with families, and reduced working hours from 44 to 33 to spread the available jobs among more people.

However, the physically grueling and dangerous nature of the work led to numerous accidents and fatalities. Reg Saunders, a 19-year-old apprentice stonemason at the Moruya Quarry, described the bloody initiation process that lasted for months. Workers standing on the Bridge hundreds of feet in the air, secured only by ropes, had to catch newly forged, scalding-hot metal rivets and bolts in buckets of water and hammer them into the beams, risking injury or death from falling objects.

In 1928, construction of the steel arch itself began, with concrete pylons rising on either side of the harbor. It would take two years for the arches to touch in the middle, forming a structure weighing 39,000 tonnes. The feat caused great anxiety among the engineers, as such an architectural achievement had never been attempted before.

The arch was self-supporting, allowing the giant cables to be removed—a historic day commemorated by the raising of British and Australian flags on both sides of the Bridge. With the arch completed, construction proceeded swiftly. By June 1931, the deck was in place and topped with asphalt, and rails were laid for trams and trains. In January 1932, the final piece of granite was laid on the northwest pylon.

The Bridge's first test came in February, with a load-testing using 96 steam locomotives laid end-to-end atop its deck. Having passed these stress tests, the Sydney Harbour Bridge was declared safe for traffic and ready to welcome the sea of humanity awaiting the harbor crossing.

On 19 March 1932, after decades of political wrangling, upheaval, and incredible feats of construction, the Sydney Harbour Bridge would finally open to the public in a grand spectacle that included fireworks and an unexpected interruption equally as explosive as the planned festivities.

The story is based on the podcast series "The Bridge: The Arch that Cut the Sky,” created with the support of the State Library of New South Wales Foundation. You can support it by listening at the thebridge.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Please note that the photographs used in this story are sourced from the State Library of New South Wales Foundation website for the podcast. These images are not our intellectual property and are used solely for non-commercial purposes.

Latest News